Table des matières

The inner ear, a delicate hub of hearing and balance, can fall prey to infections that disrupt its harmony. A detailed medical review by specialists outlines labyrinthitis—an inflammatory condition of the labyrinth—caused by bacterial, viral, protozoal, and fungal agents. This exploration, drawn from otolaryngology literature, traces the pathways of infection, their impact on auditory and vestibular function, and potential interventions. It invites reflection on how such disruptions might intersect with auditory health and therapeutic approaches like audio-psycho-phonology (APP).

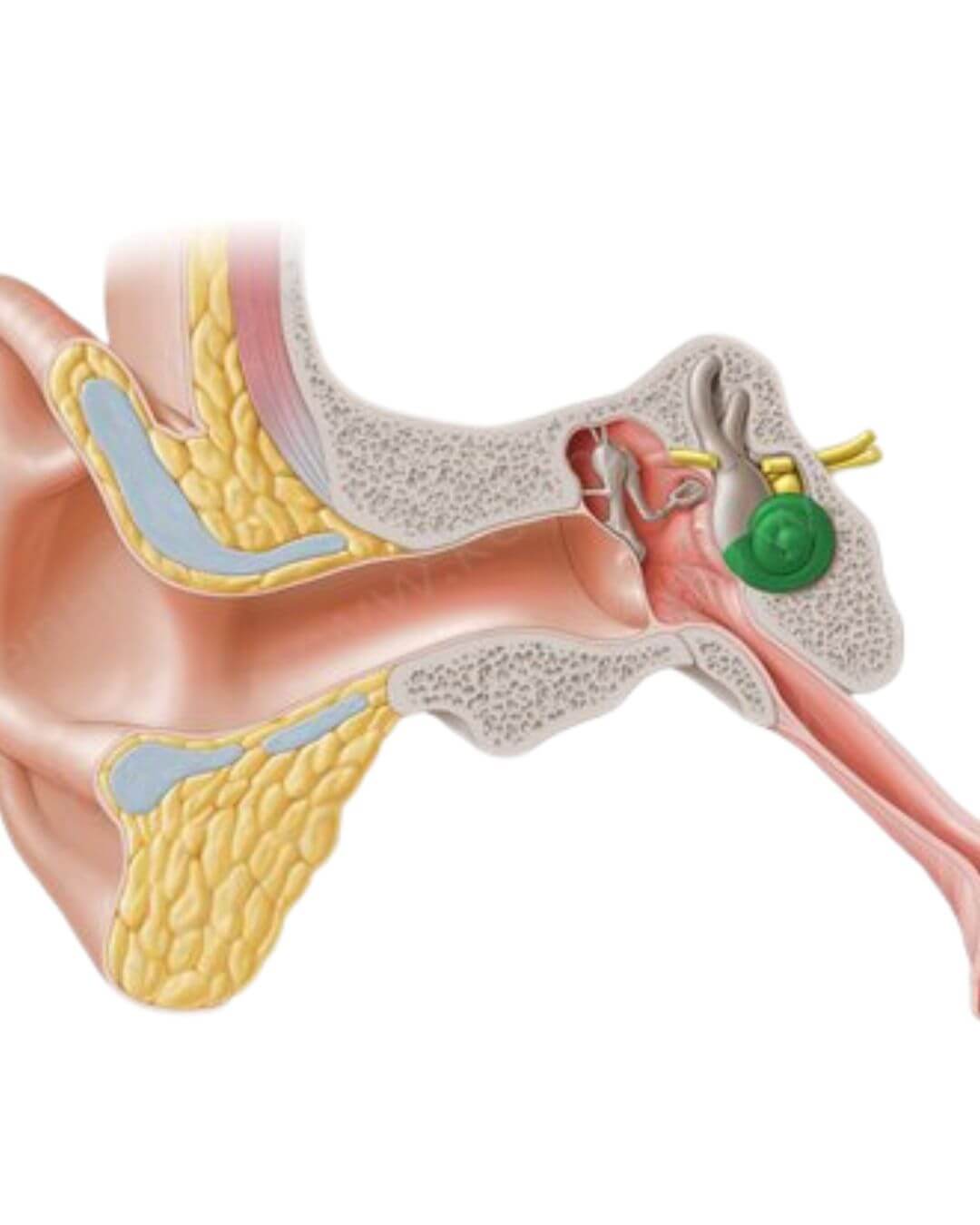

A Vulnerable Sanctuary

Labyrinthitis refers to inflammation affecting the inner ear’s bony or membranous structures, potentially isolating to the cochlea or vestibular organs or engulfing all components. Its causes span infectious origins—bacterial, viral, protozoal, and fungal—contrasted with non-infectious triggers like autoimmunity, which remain outside this focus. Infections may arise congenitally, evident at birth, or be acquired later, manifesting as an isolated ear issue or part of a systemic illness. Understanding these pathways sheds light on the ear’s susceptibility and resilience.

Pathways of Invasion

Infection reaches the labyrinth through three routes: the meninges, middle ear space, or bloodstream. Meningogenic spread, common in children due to immature immunity and a patent cochlear aqueduct, involves the internal auditory canal (IAC) or cochlear aqueduct, with leukocytes and bacteria infiltrating along the eighth cranial nerve. Tympanogenic labyrinthitis stems from middle ear or mastoid infections, often via the round window, where inflammatory cells thicken the membrane, spreading to perilymphatic spaces. Hematogenous spread, the least common, seeds pathogens via the bloodstream. These mechanisms highlight the ear’s exposure to external threats.

Bacterial Threats

Bacterial labyrinthitis divides into toxic and suppurative forms. Toxic labyrinthitis, linked to otitis media or early meningitis, involves sterile toxin penetration causing mild hearing loss or vestibular issues, often reversible with antibiotics and myringotomy. Suppurative labyrinthitis, a medical emergency, features direct bacterial invasion, progressing through serous, purulent, fibrous, and osseous stages—marked by exudate, hydrops, fibrosis, and bone deposition. Symptoms include severe vertigo, nausea, and profound hearing loss, necessitating hospitalization, antibiotics, and possibly mastoid surgery. Post-meningitic hearing loss, affecting 10-20% of cases, often stems from H. influenzae, N. meningitidis, or S. pneumoniae, with steroids showing some protective effect.

Viral Intrusions

Viral labyrinthitis manifests congenitally or as part of systemic illness, with evidence linking agents like cytomegalovirus (CMV), rubella, mumps, measles, varicella-zoster, and herpes simplex. CMV, the leading congenital cause of deafness, affects 1% of newborns, with 6,000-8,000 developing hearing loss, often bilateral and profound. Rubella, curtailed by vaccination, historically caused “cookie-bite” hearing loss in 50% of symptomatic infants. Mumps induces sudden, unilateral deafness in 0.05% of cases, while measles and varicella-zoster contribute rare but severe losses. Histopathology reveals tissue degeneration, underscoring the challenge of recovery.

Beyond Bacteria and Viruses

Protozoal toxoplasmosis and fungal infections, rare except in immunocompromised individuals, add complexity. Congenital toxoplasmosis, with a 3,000-case annual incidence, may lead to hearing loss in asymptomatic infants, mitigated by prenatal treatment. Fungal labyrinthitis, linked to Mucor, Candida, and others, causes permanent damage in high-risk groups, requiring antifungal therapy. These cases emphasize the inner ear’s vulnerability across diverse pathogens.

Clinical Manifestations

Infections present as acute cochlear labyrinthitis (sudden sensorineural hearing loss, SSNHL), vestibular labyrinthitis (vestibular neuritis), or cochleovestibular labyrinthitis. SSNHL, often viral, affects 90% unilaterally with tinnitus, improving in 30-70% of cases, especially with steroids. Vestibular neuritis causes sudden vertigo, resolving over months via compensation. Diagnosis relies on audiologic testing and imaging, with treatment ranging from supportive care to surgical intervention, tailored to severity and cause.

Reflections and Horizons

This review underscores the inner ear’s role as a sentinel of health, its infections echoing through hearing and balance. The Tomatis Method’s focus on auditory retraining might complement such cases, particularly congenital ones, by enhancing listening skills post-infection. While clinical, the data prompts curiosity about integrating auditory therapy with medical treatment. Further research could explore these synergies, offering hope to those affected.

The journey through labyrinthine infections reveals a landscape of challenge and potential recovery, urging a deeper listen to the ear’s silent pleas.

Context: Rosen, Elizabeth J., M.D., Vrabec, Jeffery T., M.D., and Quinn, Francis B., M.D. (series editor). “Infections of the Labyrinth.” Derived from Head and Neck Surgery—Otolaryngology (Bailey, B.J., ed., Lippincott-Raven, 1998) and other otolaryngology sources.